David Houliston

I am a qualified counsellor registered with the BACP and have a Diploma in Humanistic Counselling and a BSc Psychology (Honours) with Counselling. My interest in boarding school and it's effect on people's lives came from attending a missionary boarding school in Malaysia from ages 6 to 12 (see my personal journey below). Currently I am very active with Chefoo Reconsidered, made up of former students who want to look again at their time at boarding school - what it has meant for them in the past, and what it means for them now. At boarding school we learnt to survive, now there's an opportunity to go beyond survival and start living.

I live on the south coast of the UK on the border of West Sussex and Hampshire but am available to take on online clients whereever they are.

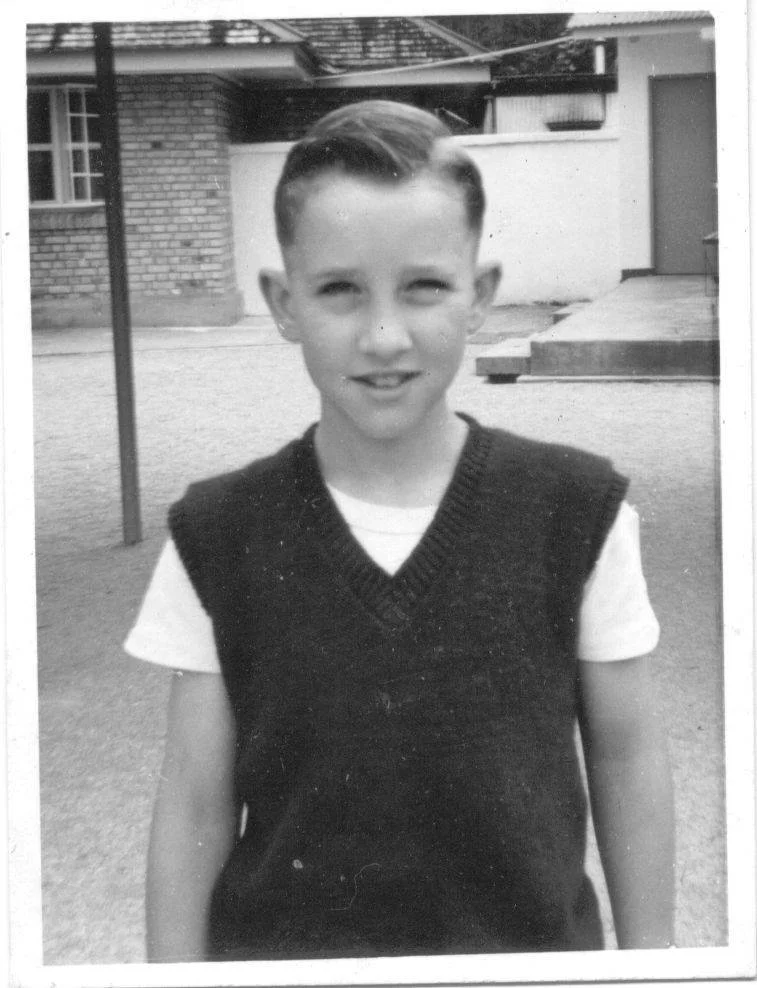

My personal journey

Early separation

On my sixth birthday in Singapore, I set off with my father for a missionary boarding school in the Cameron Highlands. Going anywhere with Dad was always an adventure. My parents had told me so much about the school — that I’d make new friends, learn clever things, and have thrilling jungle excursions. Despite my excitement as we boarded the night train, my father’s heart was breaking. He knew what I could not yet understand.

Twenty-four hours later I arrived with the others at the school in a small van. It was dark. We were given a bite to eat and then hurried into bed in our new dorm. Up in the mountains it felt cold - I was used to the heat of the tropics. The staff felt colder still. We were told not to talk after lights out. Then the switch clicked. A complete darkness I had never known filled the room. Silence, but the sound of the other boys shuffling in their beds. It was only when the lights went out that I realised the adventure had ended. For the first time since I left home my heart ached.

Longing for home

A six-year-old does not have a sense of time. I might have known it would be four and a half months before I saw my parents again, but it meant little. I was to discover how long those months really were. I longed for my mum and dad, for my brother and sister, for that warm fuzzy feeling as the family gathered in the evenings around the table after dinner at our home in Indonesia – playing, reading, teasing each other, interacting. Why did I have to stay in this place? I was sure mum and dad loved me, but why? Why didn’t they come and take me home? Why didn’t they visit me?

Learning to cope

I made friends with three of the other boys. In many ways, we grew up together. They were the best friends I ever had — but they couldn’t fill the space my parents left. I learned to cope. When I eventually returned home, I was the big shot older brother who was now worldly wise. But, in truth, I dreaded returning to the school.

In the following years my brother and sister had joined me a school. We were not encouraged to spend time as a family or to support each other. Once a week an envelope would come from our parents in Indonesia with separate letters for each of us. Later this just become one aerogramme for all of us. Times were tough and sending letters was getting expensive. One holiday, after, we didn’t return home. It was the 1960’s and there was a confrontation between Indonesia and the newly formed Malaysia. We spent the holidays with another missionary couple in West Malaysia. We spend nine months away from our parents.

By the time I was ten I was one of the “big boys”. I wasn’t a cry-baby like some of the other children. I was strong, I was also defiant and rebellious. But at the same time feeling trapped and powerless.

The aftermath

I left the school when I was twelve. My parents travelled back to their home country South Africa for a year’s furlough. When that came to an end, they headed back to South East Asia while my brother and I stayed behind, being effectively in foster care for three years until first my mother and then later my father returned. I was now in my late teens. My childhood was gone, I had been a virtual orphan from the age of six. It would take me many years to understand how deeply those separations shaped me — and how much of that little boy still lives inside me today.

How did that affect me in later life?

Of the three strategic survival personalities Duffel and Basset (2016) describe in children who attend boarding school, I recognise myself as a rebel. What I experienced felt unfair, cruel, and unjust. My anger showed up in adulthood, pushing back against authority and costing me several jobs. Yet I survived. I have had two long relationships and two wonderful children from the first of these.

The road to living

Over the last twelve years, I’ve connected with others from my boarding school who wanted to re-examine their childhood experiences. We started an informal organisation and met for a week at a time on four occasions in Malaysia and once in Japan. Together, we were surprised by how much we had in common. For years, we had hidden our ‘weirdness’ from friends, family, and colleagues. Now, we had reason to celebrate it. Feeling listened to and accepted was the first step in coming to terms with the past — not so much moving on but integrating these discoveries into living more authentically.

References

Duffell, N. and Basset, T. (2016). Trauma, Abandonment and Privilege. Routledge.

Qualifications

BSc Psychology (Honours) with Counselling

The Open University, UK

CPCAP Therapeutic Counselling Level 4 Humanistic

Professional Body

Registered Member, British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (MCAP)

Data Protection

Compliant with GDPR, Registered with the ICO, UK

Safety Check

Enhanced DBS

Insurance

Balens (cover UK and worldwide apart from the US and Canada)

Limited Company

David Houliston Counselling Limited. Reg in England & Wales 16731579